Genomics: Past, Present, and Future

Nick Boddicker, Ph.D.

nboddicker@genesus.com

Genomics is often a discussion point whenever swine producers are talking about genetics, and understandably so since genomics has promised great improvements to the swine industry. Producers want to know if the breeding company they are working with is using the most advanced technology in order to maximize profit. Most, if not all, of the major genetics companies are utilizing genomics in some way, including Genesus. Many of the technical articles that we publish pertain to genomics or projects that have a genomics component. But what about the big picture? Is genomics everything it has been hyped up to be? Has the industry benefitted from genomics?

The swine genome (total genetic make up of the pig) was officially released in 2009 and was published in 2012 (Groenen et al., 2012). The swine genome consists of 19 pairs of chromosomes, 1 of which is the sex chromosomal pair, and is approximately 2.7 billion base pairs in length, which is similar to the 3 billion base pair human genome (Bates, 2010). The figure to the right depicts base pairs in the chromosome. The majority of these base pairs are uninformative because they are the same across all pigs, but not all. The base pairs that vary from pig to pig are called SNPs, or single nucleotide polymorphisms. The first commercially available SNP chip contained ~60,000 SNPs. For the past 6 or 7 years, these 60,000 SNPs have been used to identify quantitative trait loci (QTL), which are regions in the genome that are associated with the variation in a phenotype but do not necessarily cause the variation in a phenotype. These QTL are typically in close proximity to the gene that causes the phenotypic variation.

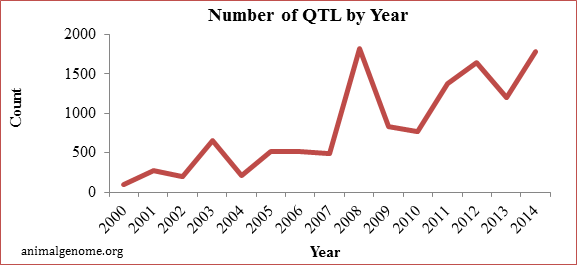

Before the release of the swine genome and the commercially available SNP chip, an average of 370 QTL were published per year. After the genome was released, an average of 1,350 QTL have been published per year, or 3.6 times more per year then before the release of the genome (animalgenome.org). These results have lead to a wealth of knowledge about genes or QTL that are affecting economically important. Below is a graph of the number of QTL reported per year since 2000.

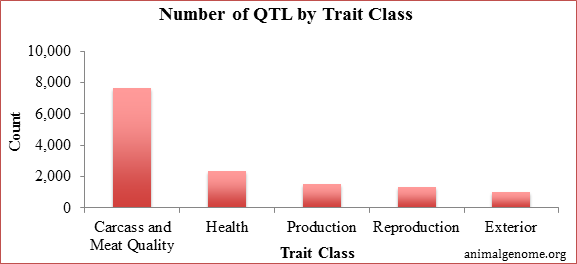

Genomic information has the largest impact on response to selection for traits that cannot be collected on selection candidates (carcass and meat quality, difficult to measure (health related), and lowly heritable traits (reproductive performance). Below is a summary of the total number of QTL by trait class that has been reported at the end of 2014. Approximately 72% of the reported QTL have been in the trait classes of carcass and meat quality and health. This does not mean that all of these QTL are being utilized within the swine industry, but clearly a lot of research has gone into identifying QTL that are associated with these traits that are difficult to select on in the nucleus. From here, it is up to each breeding company to validate the presence of these QTL within their populations before using them for genomic selection.

Research has shown that genomics can increase the rate of genetic gain by 10 to 43% for various traits (Dekkers, 2007). However, the swine industry as a whole has been slow to incorporate genomic information compared to the dairy industry. One of the primary reasons is because the commercial animals are crossbred and nucleus animals are typically pure. Therefore, there is a disconnect between purebred performance and crossbred performance. Genomics can bridge the gap if the breeding company has access to genomic and phenotypic information of crossbred animals.

The above has provided a snapshot of genomics to date and where we currently stand in the swine industry. But where is the industry going in the future with genomics? The first key area is an increase in the number of SNPs on a SNP Chip. Smaller density panels, e.g. the 60,000 SNP chip, do not capture all of the genetic variance present within a population, which means important information within the genome may not be fully captured, or captured at all. A little over 1 year ago, a new panel was released that contained ~80,000 SNPs. Research is being conducted with this new panel and early Genesus research is yielding promising results; possibly better than the original 60,000 SNP chip. The newest panel that has been developed is the 600,000 SNP chip. Genesus is one of the first, if not the first, swine genetics company to utilize this new chip and results will available in the months to come. The largest number of SNPs is sequencing the whole genome, or all 2.7 billion base pair and Genesus has already sequenced some animals within its population. It is difficult to appreciate the massive amount of data that sequencing yields, but the computer power that is required to handle that amount of data is substantial.

Other emerging areas of research that have become important since the release of the swine genome include nutrigenomics, epigenetics, and “personalized swine” medicine. Not only are geneticists utilizing genomics, nutritionist are doing research on the effect that nutrition has on the expression of genes, which translates into differences in performance. “Does a certain nutritional component in the diet alter the expression of a gene in a beneficial manner?” is one of the questions nutrigenomics can answer. An example of epigenetics is the effect the mother has on her offspring in utero. “Does the environment the mother is in during gestation have an effect on offspring performance?” is one of the questions answered through epigenetics. And finally, vaccine companies are utilizing genomics to identify vaccines that are more beneficial if a population of animals has a certain genetic make up.

Clearly genomics has benefitted the swine industry as a whole, but we have only touched the tip of the iceberg. The release of the swine genome has opened the doors to many areas of research that were not possible before. It is an exciting time to be in the swine industry and as a researcher and geneticist it is an exciting time to work in the swine genetics business in order to perform cutting edge research using the most advanced technology in order to maximize profits for our producers and customers.

References:- Animal Genomics website and database. Animalgenome.org.

- Bates, Ronald. 2010. Release of the Pig Genome! 2010 National Pork Board Swine Extenstion In-Service Conference.

- Dekkers, JCM. 2007. Marker-assisted selection for commercial crossbred performance. Journal of Animal Science. 85:2104-2114.

- Groenen, M.A, Archibals, A.L, et al. 2012. Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and evolution. Nature 491:393-398.

Categorised in: Global Tech

This post was written by Genesus